- Home

-

Leven

-

Geschriften

- TIE >

- KV >

- PPCM

- TTP >

- TP >

- E >

- EP >

-

NS - Voorreeden

>

- NS_VR01

- NS_VR02

- NS_VR03

- NS_VR04

- NS_VR05

- NS_VR06

- NS_VR07

- NS_VR08

- NS_VR09

- NS_VR10

- NS_VR11

- NS_VR12

- NS_VR13

- NS_VR14

- NS_VR15

- NS_VR16

- NS_VR17

- NS_VR18

- NS_VR19

- NS_VR20

- NS_VR21

- NS_VR22

- NS_VR23

- NS_VR24

- NS_VR25

- NS_VR26

- NS_VR27

- NS_VR28

- NS_VR29

- NS_VR30

- NS_VR31

- NS_VR32

- NS_VR33

- NS_VR34

- NS_VR35

- NS_VR36

- NS_VR37

- NS_VR38

- NS_VR39

- NS_VR40

- NS_VR41

- NS_VR42

- NS_VR43

- Filosofie

- Blog

-

Lezen

-

Omtrent Spinoza

>

- Tolstoi en Spinoza

- Spinoza en schriftvervalsing

- Ieder zijn Spinoza

- Mijn avontuur met het Operaportret

- Over de twee Spinoza's

- Brevieren... in Spinoza

- Boeken die het leven veranderen?

- Spinoza-light

- De bronzen denker aan de Paviljoensgracht in den Haag

- Spinoza en de Schone Letteren

- Benjamin DeCasseres

- Theun de Vries over Spinoza

- De ethiek van Robert Misrahi in het spoor van Spinoza

- Spinoza's Lieux de mémoire

- De tekstdoolhof van Pierre Bayle

- Vermeer en Spinoza

- Gérard de Nerval, romantische naturalist

- Graaf Stanislaus von Dunin-Borkowski S.J., Spinoza-pionier

- Lord Bertrand Russell

- Harold Foster Hallett (1886-1966)

- Het dodenmasker van Spinoza...?

- De Wereldbibliotheek en Spinoza

- Spinoza en het humanisme

- In memoriam Robert Misrahi

- De niet genoemde

- Pierre Bayle: République des Lettres

- Ed Witten, de snaartheorie en Spinoza

- Bibliografie en links

- De interlineaire Spinoza >

-

Omtrent Spinoza

>

- Bibliofilie

- Kalender/Contact

One philosopher in Rotterdam and another in Amsterdam

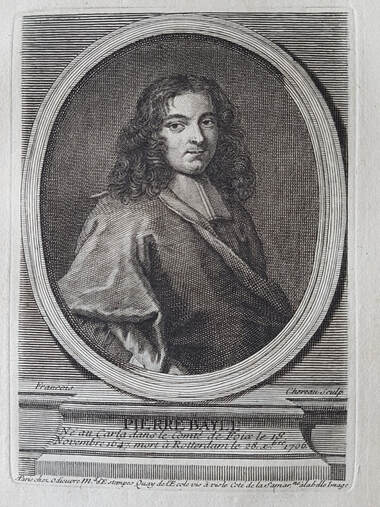

According to a longstanding tradition, Pierre Bayle (1647-1706) is known as 'le Philosophe de Rotterdam' because he lived there, worked there for 26 years, and breathed his last (1).

At the same time, a philosopher was also at work in Amsterdam and not the least: Benedictus de Spinoza (1632-1677), a younger contemporary of Pierre who survived him by 29 years. He is not known as ‘le philosophe d'Amsterdam’ but we make it up for him hic et nunc and adorn him with the title 'the Philosopher of Amsterdam'.

Pierre Bayle was born on December 18, 1647, in le Cayla-le-Comte (now Cayla-Bayle, about seven hundred inhabitants), a bastide, a small, fortified town, in the southern French department of Arriège, pays des Cathares:

(…), ce village fortifié du Carla, avec ses remparts baignés de soleil d’ou l’on découvre un paysage géométrique de sobres collines devant la grande Muraille des Pyrénées (2).

(…), ce village fortifié du Carla, avec ses remparts baignés de soleil d’ou l’on découvre un paysage géométrique de sobres collines devant la grande Muraille des Pyrénées (2).

Carla-Bayle (Google Earth)

Carla-Bayle (Google Earth)

Calvinist or Catholic?

He was born there in the family of a Calvinist pastor who was not well off and about whom history has little to tell. Pierre began his studies in 1666 at the Protestant Academy of Puylaurens. Looking for a better education, he started attending the Jesuit College of Toulouse in 1669. There he converted to Catholicism which led to tensions with his family, but after 17 months he became a Calvinist again. French law punished this form of apostasy with banishment. He therefore moved to Geneva where he continued his studies. After his studies he held posts as a tutor in Geneva and in Paris.

After a fierce fight, he managed to secure a chair in philosophy at the Protestant Academy of Sedan in 1675. He taught there for six years until Louis XIV closed this Academy in 1681. Bayle realized that he had little or no future as a Calvinist in France and decided to emigrate. He ended up in Rotterdam in the same year. Through contacts and advocacy, he became professor at the newly founded Illustrious School, together with the theologian Pierre Jurieu, a colleague of him in Sedan. After some time, both fell into discord for political reasons. Bayle lost the case and his job in 1693, so that from then on, he had to live of his pen. In that public dispute, most sided with Pierre Bayle, if we are to believe the following slack verses by Voltaire:

He was born there in the family of a Calvinist pastor who was not well off and about whom history has little to tell. Pierre began his studies in 1666 at the Protestant Academy of Puylaurens. Looking for a better education, he started attending the Jesuit College of Toulouse in 1669. There he converted to Catholicism which led to tensions with his family, but after 17 months he became a Calvinist again. French law punished this form of apostasy with banishment. He therefore moved to Geneva where he continued his studies. After his studies he held posts as a tutor in Geneva and in Paris.

After a fierce fight, he managed to secure a chair in philosophy at the Protestant Academy of Sedan in 1675. He taught there for six years until Louis XIV closed this Academy in 1681. Bayle realized that he had little or no future as a Calvinist in France and decided to emigrate. He ended up in Rotterdam in the same year. Through contacts and advocacy, he became professor at the newly founded Illustrious School, together with the theologian Pierre Jurieu, a colleague of him in Sedan. After some time, both fell into discord for political reasons. Bayle lost the case and his job in 1693, so that from then on, he had to live of his pen. In that public dispute, most sided with Pierre Bayle, if we are to believe the following slack verses by Voltaire:

Par le fougueux Jurieu, Bayle persécuté

Sera des bons esprits à jamais respecté.

Le nom de Jurieu, son Rival fanatique

N’est aujourdh’ui connu que par l’ horreur publique (3).

When Spinoza died in 1677, he was widely known as a learned philosopher. There was no mention of Bayle then. When he settled in Rotterdam at the end of December 1681 at the age of thirty-four, he was still an unknown who had not yet published a word. But by the time of his death in 1706, Bayle had become a European celebrity, though many doubted his Calvinist orthodoxy.

Waned fame

From the second half of the 19th century, Bayle's fame waned, while Spinoza's continued to rise steadily after 1677: today his works are studied all over the world. Pierre Bayle has almost disappeared from the spotlight. Completely undeserved.

Intellectual curiosity was in Pierre Bayle's blood: reading, studying, writing, and publishing filled his life. He kept up a busy correspondence (almost 1800 letters!), kept a diary for forty years, published books, filled a one-man magazine, and developed into a lexicographer with European fame. Caroline Louise Thijssen-Schoutte (1904-1961), an erudite expert on the Dutch Golden Age, wrote in this regard:

From the second half of the 19th century, Bayle's fame waned, while Spinoza's continued to rise steadily after 1677: today his works are studied all over the world. Pierre Bayle has almost disappeared from the spotlight. Completely undeserved.

Intellectual curiosity was in Pierre Bayle's blood: reading, studying, writing, and publishing filled his life. He kept up a busy correspondence (almost 1800 letters!), kept a diary for forty years, published books, filled a one-man magazine, and developed into a lexicographer with European fame. Caroline Louise Thijssen-Schoutte (1904-1961), an erudite expert on the Dutch Golden Age, wrote in this regard:

Writers are approached even after centuries, when one visits the places where they lived and worked, when one makes a pilgrimage to their birthplace, when one muses at their graves, when one walks along the roads by which they must have gone, while thinking away all modern additions. This hardly applies to Bayle: the only image that imposes itself with great pertinence on the reader of his writings and on the user of his dictionary is that of the dusty study, with a bed in the corner, the walls full of bookshelves, papers everywhere and the slender man, almost always at his desk, reading and writing, not letting himself be distracted in the summer, when through the open window the roll of a tug, the laughter or quarrel of romping children or the scream of a seagull penetrates; in the winter, early in the morning by the oil lamp, during the day a distracted look outside with the grateful thought that nothing compels him to go out since he was forbidden to lecture and come back until late in the evening, or deep into the night again by the oil lamp behind the closed curtain. Bayle receives a visit to his bachelor room with mixed feelings: the lively discourse - and usually for the visitor, exile like Bayle, French is the native language, although the accent with which the visitor speaks French sometimes betrays the Dutchman or the Englishman - is refreshing but also wearies the host, who sometimes realizes that his daily schedule is messed up. For the day's work which he had set himself was already overloaded with articles and letters that needed to be written, proofs that had to be corrected; more than once he experiences it as a chaos.

’II est bien malaise que pendant que les imprimeurs travaillent sans discontinuation, l'auteur sufise a ces trois choses, a faire la revision de deux gros volumes in folio, a les augmenter de plus d' un tiers, & a corriger les épreuves,’ sighed Bayle on December 7, 1701, when he wrote the foreword for the second edition of his gigantic undertaking, a work that went far beyond what it intended to be in the first instance: a supplement to Moréri's dictionary, teeming with errors, but such was the common fate of all the writings that Bayle set up to go far beyond the first draft (4).

’II est bien malaise que pendant que les imprimeurs travaillent sans discontinuation, l'auteur sufise a ces trois choses, a faire la revision de deux gros volumes in folio, a les augmenter de plus d' un tiers, & a corriger les épreuves,’ sighed Bayle on December 7, 1701, when he wrote the foreword for the second edition of his gigantic undertaking, a work that went far beyond what it intended to be in the first instance: a supplement to Moréri's dictionary, teeming with errors, but such was the common fate of all the writings that Bayle set up to go far beyond the first draft (4).

The fact that he and Spinoza spent their bachelor life in a rented room should not lead to the conclusion that they were both scholars in an ivory tower, far from it. They had both feet on the ground and had in no way turned away from the world: both men were up to date and à la page and followed all social developments with interest. Pierre Bayle, for example, had a fine nose for social trends and literary fashions.

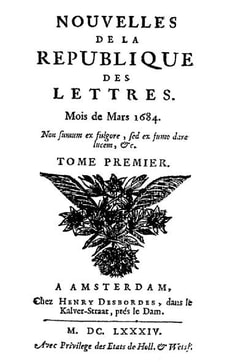

Nouvelles de la République des Lettres, mars 1684, Tome 1

Nouvelles de la République des Lettres, mars 1684, Tome 1

In the 17th century, readers were fond of literary revues and reference works. In that century, the first scholarly journals addressed a wide audience to publicize the discoveries of the new science. That seemed like something to Bayle: he wanted to publish such a magazine himself… In a letter to a friend from Amsterdam, he writes that several acquaintances (also in Paris) gave him positive advice about this:

'Ils m'ont dit, qu'il faut tenir un milieu entre les Nouvelles de Gazette et les Nouvelles de pure science, afin que les Cavaliers et les Dames, et en général mille personnes qui lisent et qui ont de l'esprit, sans être Savans, se divertissent à la lecture de nos Nouvelles.' (5)

Eventually he signed a contract with the Amsterdam publisher Henri Desbordes (+1722) to publish a revue: from 1684 to 1687 he published Nouvelles de la République des Lettres, a one-man magazine that he wrote in full himself. His initiative was successful, and Bayle soon became known in Europe as 'a man with an opinion'.

'Ils m'ont dit, qu'il faut tenir un milieu entre les Nouvelles de Gazette et les Nouvelles de pure science, afin que les Cavaliers et les Dames, et en général mille personnes qui lisent et qui ont de l'esprit, sans être Savans, se divertissent à la lecture de nos Nouvelles.' (5)

Eventually he signed a contract with the Amsterdam publisher Henri Desbordes (+1722) to publish a revue: from 1684 to 1687 he published Nouvelles de la République des Lettres, a one-man magazine that he wrote in full himself. His initiative was successful, and Bayle soon became known in Europe as 'a man with an opinion'.

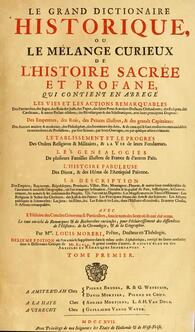

Moréri. Grande Dictionaire Historique. Edition 1716, Tome 1

Moréri. Grande Dictionaire Historique. Edition 1716, Tome 1

Reference works by numbers

The 17th century was the century of reference works and dictionaries. That, too, had not escaped Bayle's attention. He was particularly interested in the dictionary of the French priest Moréri (1643-1680) published in 1674 (6). Moréri's work was an overwhelming success and reprinted at least twenty times between 1674 (one volume) and 1759 (10 volumes!). But it was teeming with mistakes! Nevertheless the priests dictionary was translated into English, German, Dutch and Spanish. Bayle also wanted to publish his own dictionary and at the same time correct Moréri's mistakes, and eventually he did!

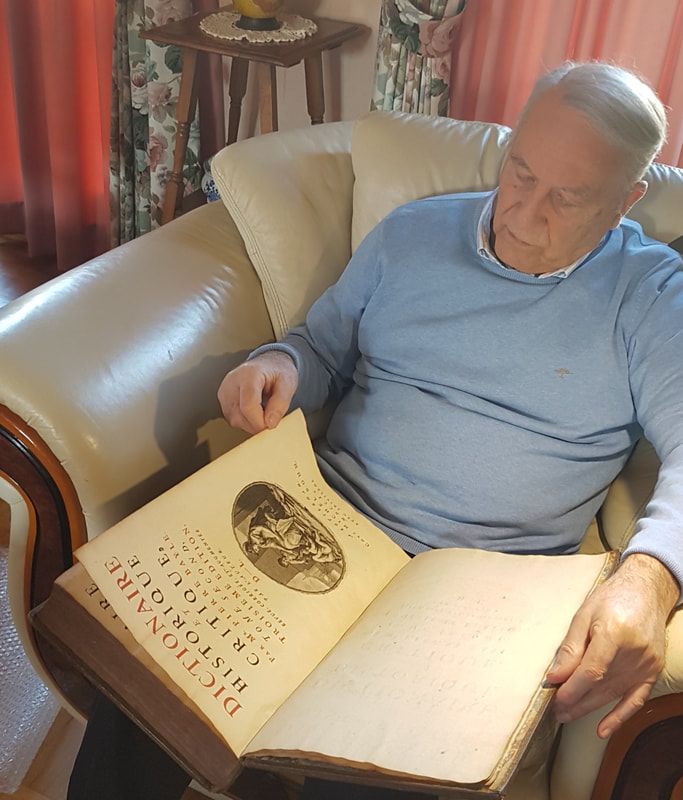

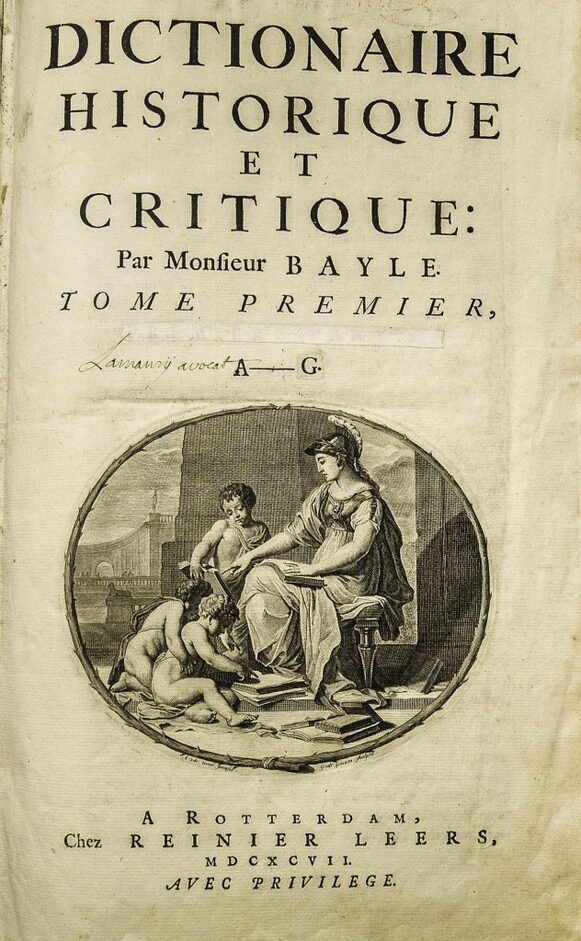

Thus, as previously mentioned by Thijssen-Schoutte, the first edition of his magnum opus the Dictionaire (sic) historique et critique was published in 1697. This dictionary grew into a voluminous work of four folio volumes and about four thousend pages (7). His DHC was indeed a success: no less than 12 editions were published, the last of which dates from 1830. The book was read all over Europe, and as far as in Russia. It contains very progressive thoughts and is therefore a precursor to Diderot-d'Alembert's Encyclopédie.

The 17th century was the century of reference works and dictionaries. That, too, had not escaped Bayle's attention. He was particularly interested in the dictionary of the French priest Moréri (1643-1680) published in 1674 (6). Moréri's work was an overwhelming success and reprinted at least twenty times between 1674 (one volume) and 1759 (10 volumes!). But it was teeming with mistakes! Nevertheless the priests dictionary was translated into English, German, Dutch and Spanish. Bayle also wanted to publish his own dictionary and at the same time correct Moréri's mistakes, and eventually he did!

Thus, as previously mentioned by Thijssen-Schoutte, the first edition of his magnum opus the Dictionaire (sic) historique et critique was published in 1697. This dictionary grew into a voluminous work of four folio volumes and about four thousend pages (7). His DHC was indeed a success: no less than 12 editions were published, the last of which dates from 1830. The book was read all over Europe, and as far as in Russia. It contains very progressive thoughts and is therefore a precursor to Diderot-d'Alembert's Encyclopédie.

Dictionaire Historique et Critique, title page de la première édition (1694).

Dictionaire Historique et Critique, title page de la première édition (1694).

The importance of the Dictionary is on more than one level. Because of language and style, it is a part of French literature, and it occupies there a unique place due to its content, form, and typography. It is an important historical source that also informs us in seventy articles about aspects of the Dutch Golden Age and it also contains primary biographical information about Pierre Bayle himself. Moreover, it is a work that can also be considered philosophical because the articles often testify to the philosophical views of the author as well as those of his 17th century contemporaries.

Not all editions of the DHC are of equal historical importance. The most important of course, is the editio princeps of 1697, published in two volumes in folio. The 1720 edition presents itself as the third but is in fact the fourth and was published 14 years after the author's death containing for the first time also his additions, which makes this edition special.

Typographically, this edition is also a masterpiece: the articles follow one another for the first time, immediately after the comments of the previous article, and all have beautiful page mirrors. The fourth edition of 1730, in fact the fifth, is generally regarded as definitive.

Not all editions of the DHC are of equal historical importance. The most important of course, is the editio princeps of 1697, published in two volumes in folio. The 1720 edition presents itself as the third but is in fact the fourth and was published 14 years after the author's death containing for the first time also his additions, which makes this edition special.

Typographically, this edition is also a masterpiece: the articles follow one another for the first time, immediately after the comments of the previous article, and all have beautiful page mirrors. The fourth edition of 1730, in fact the fifth, is generally regarded as definitive.

Steppingstones to the Enlightenment

Anyone who studies Spinoza soon finds himself in the waters of Pierre Bayle. He developed a lasting but irritated interest in Spinoza. Both never saw each other in person, but from Bayle's correspondence we know that he became acquainted with Spinoza's Theological-Political Treatise around 1670 and that he bought himself a copy of Spinoza's Opera Posthuma (1677). In the first edition of the DHC (1697) Bayle wrote a long article about the life and teachings of the 'Philosopher of Amsterdam'. It belongs to the 'early biographies' of Spinoza (8). The DHC Spinoza article was translated into Dutch within a year. If Spinoza acquired wider European fame in the 18th-19th century, it was partly thanks to DHC: Catherine II of Russia, for example, got to know Spinoza better through Bayle's Dictionaire in her library. The many reprints of that dictionary have ensured that the image he constructed of Spinoza's life and work (far from objective) still lives on in the collective memory of many Europeans today...

Spinoza and Bayle are important steppingstones on the way to the Enlightenment and therefore also of great historical importance. In the last century, Bayle's role as an historical precursor has been overemphasized at the expense of a fundamental study of his literary and philosophical significance for his time. The 1959 commemoration of the 250th anniversary of Bayle's death called for a revaluation and even a rediscovery of this giant. As far as I could tell, a plea with only moderate success. At the beginning of the 20th century, Jonathan Israel (Princeton University) wrote a historical masterpiece about the Enlightenment that is as erudite as it is extensive. In one of the parts, Spinoza is portrayed as pioneering the so-called Radical Enlightenment (9). It is a well-founded historical interpretation that in no way detracts from the individuality of our philosopher's life and work but was criticized by colleagues.

The DHC is still not appreciated at its full value but, let there be no doubt, Bayle's Dictionaire is an absolute masterpiece: particularly historical-critical and incredibly erudite in its time: a letter-monument that was realized by a man with an unbridled energy who let his 'curiosité' (intellectual curiosity) prevail over the joys of life.

Anyone who studies Spinoza soon finds himself in the waters of Pierre Bayle. He developed a lasting but irritated interest in Spinoza. Both never saw each other in person, but from Bayle's correspondence we know that he became acquainted with Spinoza's Theological-Political Treatise around 1670 and that he bought himself a copy of Spinoza's Opera Posthuma (1677). In the first edition of the DHC (1697) Bayle wrote a long article about the life and teachings of the 'Philosopher of Amsterdam'. It belongs to the 'early biographies' of Spinoza (8). The DHC Spinoza article was translated into Dutch within a year. If Spinoza acquired wider European fame in the 18th-19th century, it was partly thanks to DHC: Catherine II of Russia, for example, got to know Spinoza better through Bayle's Dictionaire in her library. The many reprints of that dictionary have ensured that the image he constructed of Spinoza's life and work (far from objective) still lives on in the collective memory of many Europeans today...

Spinoza and Bayle are important steppingstones on the way to the Enlightenment and therefore also of great historical importance. In the last century, Bayle's role as an historical precursor has been overemphasized at the expense of a fundamental study of his literary and philosophical significance for his time. The 1959 commemoration of the 250th anniversary of Bayle's death called for a revaluation and even a rediscovery of this giant. As far as I could tell, a plea with only moderate success. At the beginning of the 20th century, Jonathan Israel (Princeton University) wrote a historical masterpiece about the Enlightenment that is as erudite as it is extensive. In one of the parts, Spinoza is portrayed as pioneering the so-called Radical Enlightenment (9). It is a well-founded historical interpretation that in no way detracts from the individuality of our philosopher's life and work but was criticized by colleagues.

The DHC is still not appreciated at its full value but, let there be no doubt, Bayle's Dictionaire is an absolute masterpiece: particularly historical-critical and incredibly erudite in its time: a letter-monument that was realized by a man with an unbridled energy who let his 'curiosité' (intellectual curiosity) prevail over the joys of life.

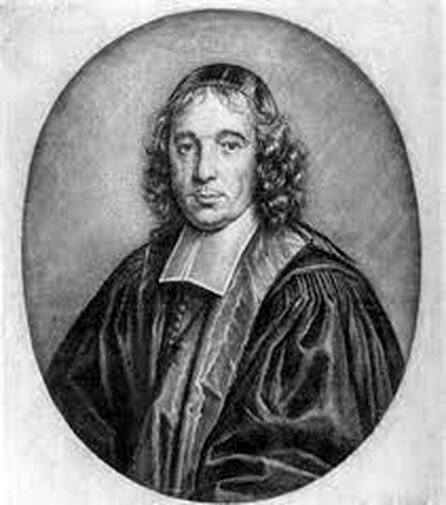

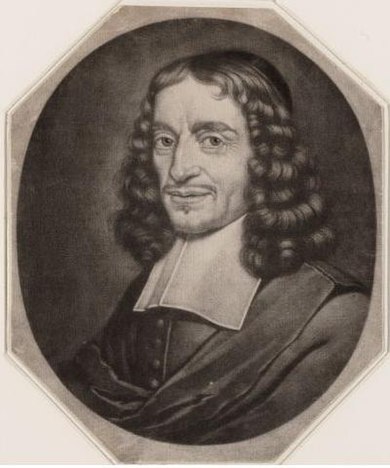

Geeraert Brandt (1626-1685)

Geeraert Brandt (1626-1685)

The death of Bayle

In the winter of 1706, on December 28 at 9 a.m., Pierre Bayle died at the age of 59 years, 1 month and 10 days. The circumstances of his death are reminiscent of those of the Philosopher of Amsterdam: like Spinoza, Bayle died on a frosty winter morning, lonely in a rented room, and like Spinoza from the effects of a lung disease. He was buried in a mass grave in the Walloon church in Rotterdam: did his Calvinist heterodoxy or his financial situation play a role in this sad and shabby interment?

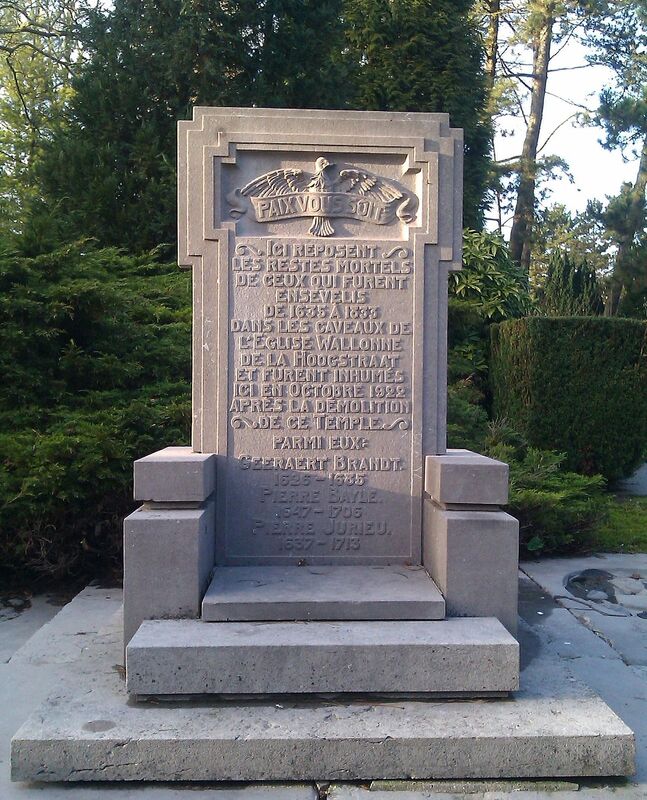

In 1922 that church was demolished and the people who were buried there between 1635 and 1833 were interred just outside Rotterdam in the General Cemetery of Crooswijk, on the left bank of the Rotte. A tombstone with French text (it was a 'Walloon' Church) recalls the transfer and the ossuary. Pierre Bayle is mentioned on that stele along with the other Pierre, Pierre Jurieu, yes, his archenemy and together with a third who received the honour of first place (10). Even in 1922 the narrow-minded Calvinists could not muster much sympathy for Bayle…

In the winter of 1706, on December 28 at 9 a.m., Pierre Bayle died at the age of 59 years, 1 month and 10 days. The circumstances of his death are reminiscent of those of the Philosopher of Amsterdam: like Spinoza, Bayle died on a frosty winter morning, lonely in a rented room, and like Spinoza from the effects of a lung disease. He was buried in a mass grave in the Walloon church in Rotterdam: did his Calvinist heterodoxy or his financial situation play a role in this sad and shabby interment?

In 1922 that church was demolished and the people who were buried there between 1635 and 1833 were interred just outside Rotterdam in the General Cemetery of Crooswijk, on the left bank of the Rotte. A tombstone with French text (it was a 'Walloon' Church) recalls the transfer and the ossuary. Pierre Bayle is mentioned on that stele along with the other Pierre, Pierre Jurieu, yes, his archenemy and together with a third who received the honour of first place (10). Even in 1922 the narrow-minded Calvinists could not muster much sympathy for Bayle…

Reading in DHC: Jamais sans Paroles

For my part, I cannot honour Pierre Bayle better than by quoting the laudatory words with which Hubert Bost concludes his Bayle biography:

For my part, I cannot honour Pierre Bayle better than by quoting the laudatory words with which Hubert Bost concludes his Bayle biography:

‘Essayist, polemiste, journalist, historien, philosophe, homme de lettres, savant, erudit, critique… tout cela lui convient. Mais, avant tout, homme libre et penseur libre (11)’.

There are such days when I like to lose myself in the text-ocean of Bayle's Dictionaire historique et critique, and I count myself fortunate to be able to do so in a well-preserved copy of the original third edition of 1720.

References

(1) Desiderius Erasmus (1466-1536) was born in Rotterdam but lived there for only a few years. That did not prevent him from referring to himself as 'Erasmus of Rotterdam'.

(2) Paul Dibon, Redécouverte de Bayle, p. VII, in Pierre Bayle, le philosophe de Rotterdam, études et documents, Amsterdam, 1959.

(3) Voltaire, IIIème Discourse de l'Homme. De l'envie, v. 73-76, quoted in E. Labrousse, Notes sur Bayle, Paris, 1987, p. 95.

(4) C.L. Thijssen-Schoutte, The Philosopher of Rotterdam: Pierre Bayle, 1959, pp. 227-253. This essay written to commemorate the 250th anniversary of Bayle's death can be read (in Dutch) on the net:

https://rjb.x-cago.com//GARJB/1956/12/19561231/GARJB-19561231-0251/story.pdf (without reference to the source of the article)

(5) Letter quoted in H.C. Hazewinkel, Pierre Bayle à Rotterdam, in Paul Dibbon, o.c., p. 28.

(6) Louis Moréri, Grand Dictionnaire historique, ou la mélange curieux de l' histoire sacrée et profane, Lyon, 1674.

(7) Pierre Bayle, Dictionaire historique et critique, third edition, Rotterdam, 1720, in f°. I use this edition, in reality the fourth, 'edited' by Prosper Marchand and published in Rotterdam by Michel Bohm. The comments have their final order.

(8) See on this web site, button Biographies.

(9) Jonathan I. Israel, Radical Enlightenment, Franeker, third edition 2010, 944 pages!

(10) Geeraert Brandt (1626-1685) was a Calvinist preacher and man of letters born in Amsterdam. He wrote an equally well-known and meritorious biography about Admiral de Ruyter published posthumously in 1687. Bayle is the second to be mentioned and Jurieu is the last.

(11) Hubert Bost, Pierre Bayle, Paris, 2006, p., 519.

(1) Desiderius Erasmus (1466-1536) was born in Rotterdam but lived there for only a few years. That did not prevent him from referring to himself as 'Erasmus of Rotterdam'.

(2) Paul Dibon, Redécouverte de Bayle, p. VII, in Pierre Bayle, le philosophe de Rotterdam, études et documents, Amsterdam, 1959.

(3) Voltaire, IIIème Discourse de l'Homme. De l'envie, v. 73-76, quoted in E. Labrousse, Notes sur Bayle, Paris, 1987, p. 95.

(4) C.L. Thijssen-Schoutte, The Philosopher of Rotterdam: Pierre Bayle, 1959, pp. 227-253. This essay written to commemorate the 250th anniversary of Bayle's death can be read (in Dutch) on the net:

https://rjb.x-cago.com//GARJB/1956/12/19561231/GARJB-19561231-0251/story.pdf (without reference to the source of the article)

(5) Letter quoted in H.C. Hazewinkel, Pierre Bayle à Rotterdam, in Paul Dibbon, o.c., p. 28.

(6) Louis Moréri, Grand Dictionnaire historique, ou la mélange curieux de l' histoire sacrée et profane, Lyon, 1674.

(7) Pierre Bayle, Dictionaire historique et critique, third edition, Rotterdam, 1720, in f°. I use this edition, in reality the fourth, 'edited' by Prosper Marchand and published in Rotterdam by Michel Bohm. The comments have their final order.

(8) See on this web site, button Biographies.

(9) Jonathan I. Israel, Radical Enlightenment, Franeker, third edition 2010, 944 pages!

(10) Geeraert Brandt (1626-1685) was a Calvinist preacher and man of letters born in Amsterdam. He wrote an equally well-known and meritorious biography about Admiral de Ruyter published posthumously in 1687. Bayle is the second to be mentioned and Jurieu is the last.

(11) Hubert Bost, Pierre Bayle, Paris, 2006, p., 519.