- Home

-

Leven

-

Geschriften

- TIE >

- KV >

- PPCM

- TTP >

- TP >

- E >

- EP >

-

NS - Voorreeden

>

- NS_VR01

- NS_VR02

- NS_VR03

- NS_VR04

- NS_VR05

- NS_VR06

- NS_VR07

- NS_VR08

- NS_VR09

- NS_VR10

- NS_VR11

- NS_VR12

- NS_VR13

- NS_VR14

- NS_VR15

- NS_VR16

- NS_VR17

- NS_VR18

- NS_VR19

- NS_VR20

- NS_VR21

- NS_VR22

- NS_VR23

- NS_VR24

- NS_VR25

- NS_VR26

- NS_VR27

- NS_VR28

- NS_VR29

- NS_VR30

- NS_VR31

- NS_VR32

- NS_VR33

- NS_VR34

- NS_VR35

- NS_VR36

- NS_VR37

- NS_VR38

- NS_VR39

- NS_VR40

- NS_VR41

- NS_VR42

- NS_VR43

- Filosofie

- Blog

-

Lezen

-

Omtrent Spinoza

>

- Tolstoi en Spinoza

- Spinoza en schriftvervalsing

- Ieder zijn Spinoza

- Mijn avontuur met het Operaportret

- Over de twee Spinoza's

- Brevieren... in Spinoza

- Boeken die het leven veranderen?

- Spinoza-light

- De bronzen denker aan de Paviljoensgracht in den Haag

- Spinoza en de Schone Letteren

- Benjamin DeCasseres

- Theun de Vries over Spinoza

- De ethiek van Robert Misrahi in het spoor van Spinoza

- Spinoza's Lieux de mémoire

- De tekstdoolhof van Pierre Bayle

- Vermeer en Spinoza

- Gérard de Nerval, romantische naturalist

- Graaf Stanislaus von Dunin-Borkowski S.J., Spinoza-pionier

- Lord Bertrand Russell

- Harold Foster Hallett (1886-1966)

- Het dodenmasker van Spinoza...?

- De Wereldbibliotheek en Spinoza

- Spinoza en het humanisme

- In memoriam Robert Misrahi

- De niet genoemde

- Pierre Bayle: République des Lettres

- Ed Witten, de snaartheorie en Spinoza

- Bibliografie en links

- De interlineaire Spinoza >

-

Omtrent Spinoza

>

- Bibliofilie

- Kalender/Contact

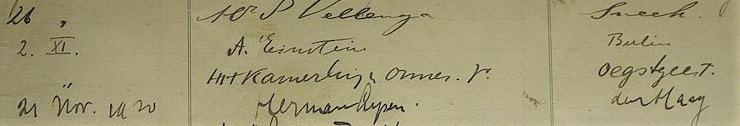

Einstein (1879-1955) admired Benedictus Spinoza. On November 2, 1920, he visited Spinoza’s house in Rijnsburg (near Leiden, Holland). His signature is in the guestbook. When Einstein was once asked what his views on God were, he replied, "I believe in Spinoza's God who reveals himself in the orderly harmony of what exists, not in a God who concerns himself with the fates and actions of human beings." Incidentally, Spinoza is mentioned more than once in Einstein's texts. There is also a eulogy of Spinoza's Ethics written by Einstein. Perhaps it was written on his visit to Rijnsburg or shortly afterwards. The poem testifies to his interest and admiration for Spinoza and his Magnum Opus.

ExplanationIn his poetry Albert Einstein emphasizes the unique and superhuman thought achievement that Spinoza accomplished in writing down his Ethica, ordine geometrico demonstrata. No one will be able to imitate him, says Einstein. Those who think they can follow in Spinoza's footsteps will likely return from a bare journey. In the last stanza, Einstein suggests that for the higher spiritual life one must be born, understand, be determined. First stanza Einstein loves Spinoza. He has no words for his affection ... this shortage of words is an experience known to everyone. Spinoza had to deal with it occasionally and spoke of a ‘shortage of words.’ Einstein, however, fears that Spinoza, as a thinker and as a human being who lived by his teachings, made an exceptional and hard to match achievement. Second stanza An average person (for Spinoza this is a member of the masses, the crowd, the people) cannot tempt you to a higher spiritual life. Intellectual love for God (amor dei intellectualis) leaves him cold and does not belong in the slightest to his sphere of interest, he is shackled by the materiality of life. Third stanza Ordinary people are not interested in a higher spiritual life: it gives them shivers and leaves them freezing cold. Making room for reason and reason in life is not an option: they are usually guided by fantasy and sentiment. The life of the common man revolves around property, wife, honour, and home: a reference to wealth, sensuality, in the first part of his Treatise on the Emendation of the Intellect (Ref. §1- §16, Bruder). Fourth stanza This situation reminds Einstein of the Baron von Münchhausen, an imaginative novelist who experienced the most wonderful adventures, described in 1785 by Rudolf Erich Raspe. Einstein finds his Münchhausen association somewhat strange and therefore asks the reader for an excuse: to mention the lie baron in the same breath with Spinoza, a passionate truth-seeker is indeed a bit daring. But Einstein simply wants to emphasize that Spinoza's life and achievements in thinking are just as exceptional and (almost) as impossible as the Münchhausen story that is alluded to. Fifth stanza Anyone who now quickly concludes that the teachings of Spinoza can also lift people out of the swamp of life should not miss out: not everyone is reserved for the higher, i.e., not everyone is suitable for setting the true and highest good as the ultimate goal of life. Spinoza did that himself, but not without effort. Anyone can read about it in the above section of the Treatise on the Emendation of the Intellect. The last line of Einstein's poem echoes the very last (not very encouraging) sentence of Spinoza's Ethics, a sentence he (slightly adapted) from Cicero (1st century BC): SED OMNIA PRAECLARA TAM DIFFICILIA QUAM RARA SUNT. |

AuteurWilly Schuermans (...) uitgaande van den gezonden stelregel, dat men zich niet boven SPINOZA verheven moet achten voor en aleer men hem begrepen heeft. Willem Meijer (1903) SKL (Spinoza kring Lier)

Platform voor de studie en de verspreiding van het gedachtegoed van Benedictus Spinoza (1632-1677) Doorzoek de hele blog alfabetisch op titels en persoonsnamen.

Categorieën

Alles

Foutje ontdekt in een blogbericht? Meld het op

[email protected] Mijn andere sites! |